Science in the Age of Enlightenment, a social phenomenon

Few centuries have loved science as much as the Age of Enlightenment, which demonstrated unprecedented enthusiasm for technical and scientific phenomena. The era, as we know, was one of firm belief in progress of all kinds, and its “taste” for science and technology, as contemporaries referred to it, stemmed from this confidence. Science thus spilled out of the ivory towers of academia and became available to a broader audience, composed of curious observers and aficionados. The latter belonged to high society, as both aristocrats and rich bourgeois from the world of trade and finance began to take an interest in a range of disciplines previously reserved for erudite scholars: physics, chemistry, natural history, and of course mechanics. The attention they devoted to scientific knowledge led them to set up full-fledged experimental laboratories in their homes, with some creating physics ‘cabinets’ or assembled natural history collections. The market for finely crafted scientific instruments was actively explored by wealthy purchasers who acquired microscopes, barometers, domestic planetariums and all kinds of devices combining scientific purpose with elegant design. Collecting scientific objects thus became a full-fledged trend, like science itself, henceforth considered to be part of the social sphere.

Educating a new public

The taste for science and technology was also expressed by the emergence of scientific teaching. Public classes were set up in large cities and provinces. Mainly intended for adults, these free or fee-paying lessons were organised by institutions as well as private individuals. They aimed at providing instruction, as well as convincing and fascinating audiences. The demonstrations conducted on town squares, at trade fairs or in private homes were all part of the same trend. Seeking to astonish while delighting the eyes, they often represented a form of showmanship. That is because fashionable science in the Age of Enlightenment did not aim to be serious, but rather to explain or justify phenomena by combining usefulness with a pleasing experience. From the 1740s onwards, physics stirred a great deal of enthusiasm thanks to the classes and demonstrations given by Jean-Antoine Nollet, also known as Abbé Nollet (1700-1770), who introduced high society to the mysteries of electricity. Chemistry was taught by Gabriel-François Rouelle (1703-1770), whose lessons were attended by Jean-Jacques Rousseau himself. Meanwhile, botanical science attracted public favour from the 1770s onwards, and just before the French Revolution, hot-air balloons began to attract crowds.

Horology at the confluence of skills

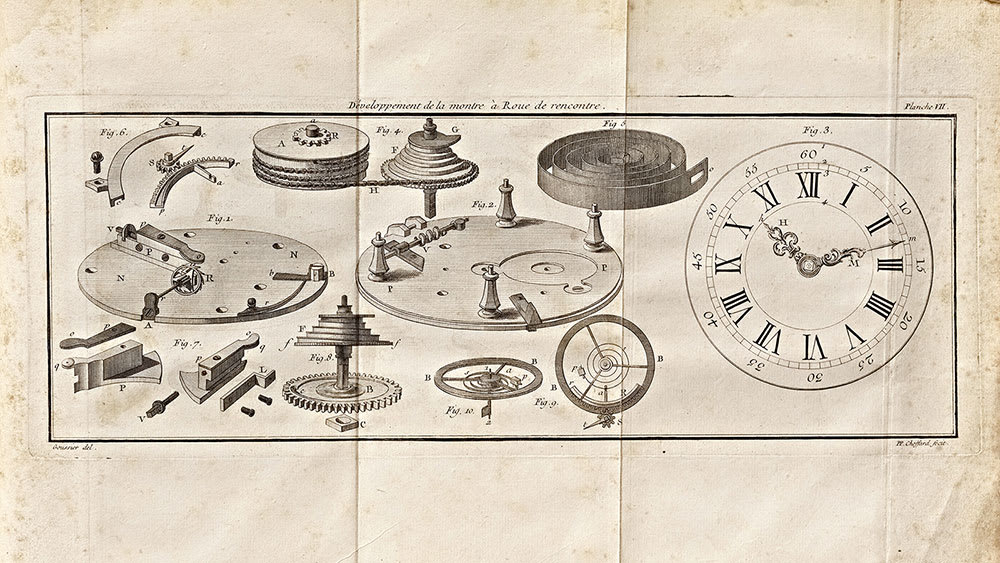

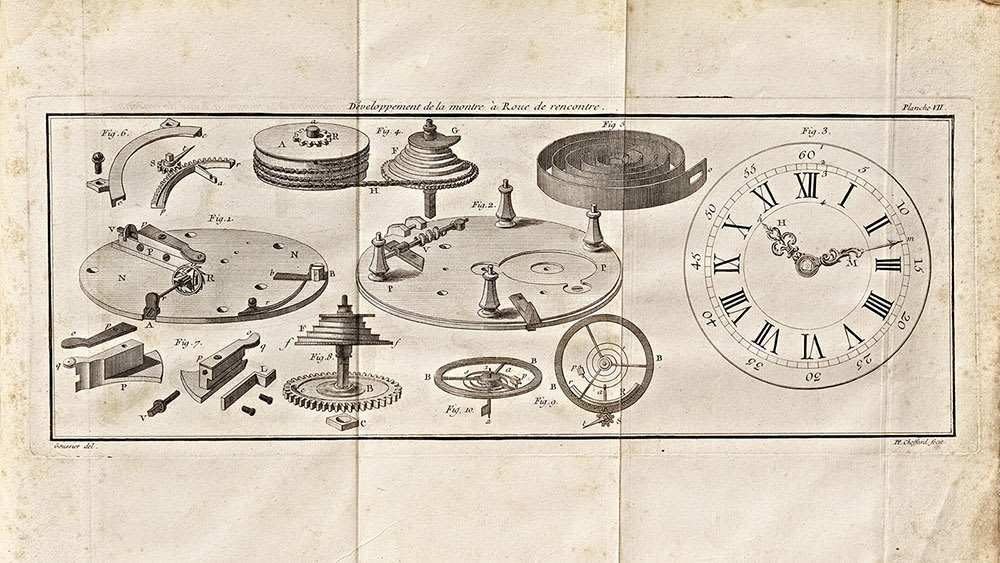

Mechanical knowledge, spearheaded by horology in the 18thcentury, did not lag behind amid this craze. Exhibitions of automatons, moving spheres, pendulums and complication watches enthralled spectators, dazzled by the evocative power of these objects and the technical expertise they encapsulated. In parallel, the progress made by horology in the field of tools also benefited other scientific realms of endeavour, notably the construction of scientific devices. At a time when worldly-wise, fashionable science in general demanded visual pleasure, considerable importance was also devoted to the beauty of mechanical objects. This focus on aesthetics, which imposed complex technical challenges on horologists and mechanical engineers, also enabled artisans to confirm the full breadth of their competencies: horology in particular lay at the confluence of these skills, as an artistic craft as well as a technical, even scientific profession.

Technical books as promotional instruments

Horology also played an active part in the phenomenon of fashionable science by means of technical books, an area of the publishing market that experienced substantial growth between the 1720s and 1780s. Books were indeed a powerful instrument of popularisation which, like the various classes and demonstrations, were a response to the demand for technical instruction among the elite. Some horologists from the Age of Enlightenment accordingly began to share their thoughts on the field in writing, starting with Antoine Thiout (1692-1767), whose Traité de l’horlogerie, méchanique et pratique (Treatise on mechanical and practical horology) was published in 1740, as well as Jean-André Lepaute (1720-1789), who penned a Traité d’horlogerie (Horology treatise) that came out in 1755. Their writings cannot be summed up as mere manuals destined to initiate the public into the art of horology. Through describing various models, their components and their operating principles, they were expounding upon horological expertise itself. Technical books thus became crucial promotional tools, whose authors often dedicated them to high-ranking members of the aristocracy so as to ensure the latters’ protection. These treatises advocated an exceptional art that was both beautiful and useful, while highlighting the knowledge of those practicing it.

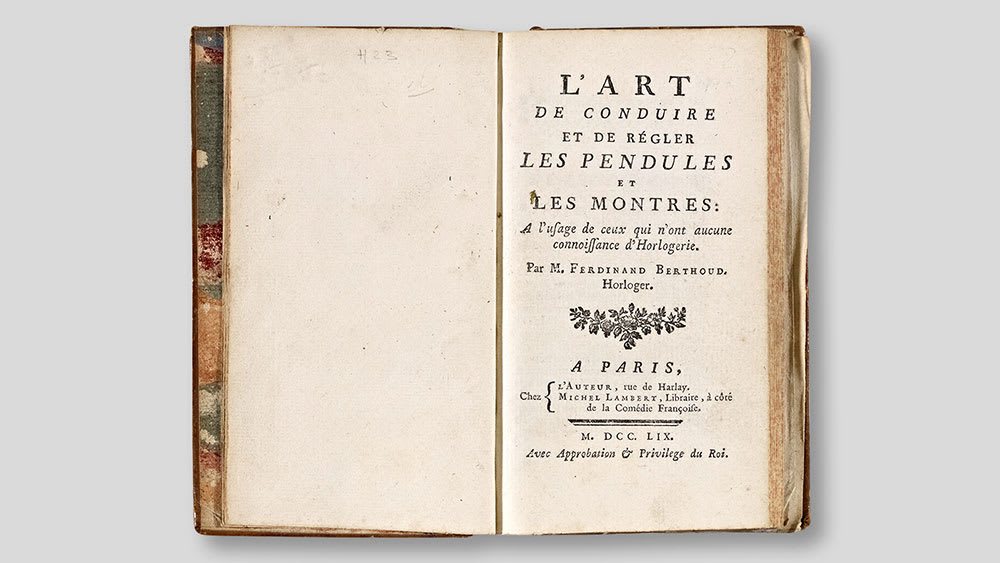

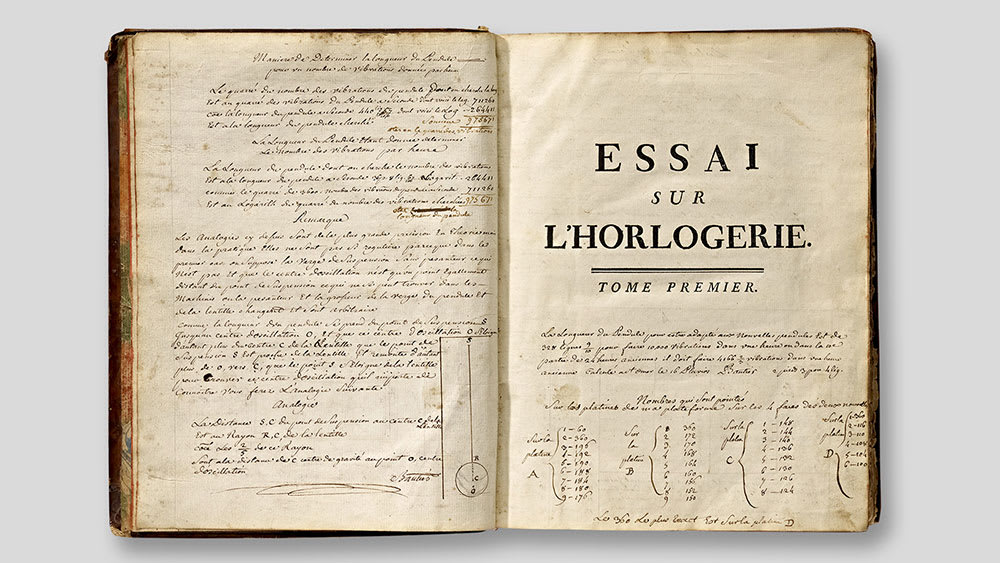

Ferdinand Berthoud was supremely aware of the value of this means of communication that secured the reputation of artists along with the favours of a wealthy clientele. This conviction incited him to write the L’art de conduire et de régler les pendules et les montres (The art of operating and adjusting clocks and watches), published in 1759; and his Essai sur l’horlogerie (Essay on Horology), 1763, which was intended for artisans, but above all for curious individual, enthusiasts and connoisseurs. He displayed an impressive capacity for popularising concepts, along with a remarkable writing style, thereby setting himself apart from his predecessors. He also stood out by his independence: at a time when he had not yet been awarded the title of “Horloger Mécanicien du Roi et de la Marine” (Clockmaker-Mechanic by appointment to the King and Navy), Berthoud took the independent decision to share his knowledge by writing in his own name.

Next article

The Art of Horlogy