Communicating with the public

The 18th century passion for science was accompanied by strong demand for technical knowledge emanating from non-specialists and keenly perceived by horologists in the Age of Enlightenment. Ferdinand Berthoud in particular grasped in his youth already the importance of making the principles of horological expertise known a broad audience. In May 1753 of the Journal helévtique, he published the “Lettre sur l’horlogerie” (Letter on Horology) which he dedicated to his fellow countryman Pierre-Jaquet Droz, the clockmaker from La Chaux-de- Fonds who had journeyed to Paris that year. Berthoud’s intention to reach a broad audience is highlighted by his choice of the Journal helvétique, which was printed in Neuchâtel and represented the most important periodical in French-speaking Switzerland at the time. It also served as a reminder of Berthoud’s origins, although in the text himself he introduces himself as a horologist fully integrated within the Parisian circle of his profession. The article comments on the state of French horology and praises certain fi gures such as Henry Sully, Julien Le Roy and Pierre de Rivaz for their contributions to its reputation. And there is no doubt about the fact that Berthoud by then indeed belonged to the horological elite of Paris, since he was awarded the much-coveted maîtrise (master clockmaker title) in December 1753.

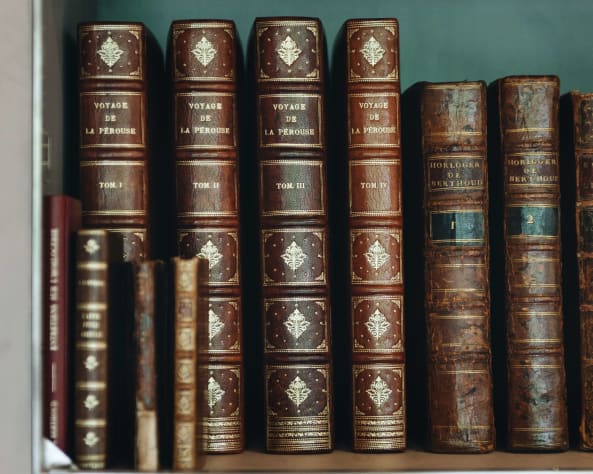

The master horologist’s talent for popularising complex

While the “Lettre sur l’horlogerie” provided a fi rst glimpse of Berthoud’s taste for didactic explanations, it was only with L’Art de conduire et de régler les pendules et les montres(1759) that the master-watchmaker truly began the task of popularising knowledge. He specifi cally addressed his work to “those who have no knowledge of watchmaking” and adopted the approach of the fashionable science of his era, which was to educate while entertaining: “I did not wish to enter into excessive details […] for fear of becoming too long-winded and too abstract & and thereby to put off those who would like to have fun”. The result is a book published in a small duodecimo format, comprising 15 brief articles written in simple language on the theme of adjusting watches and clocks. The underlying purpose of producing a book that was both understandable and pleasant is confi rmed by the four refi ned plates that complement the explanations. Designed and engraved by Pierre-Philippe Choffard, a famous ornamentalist, they apply a rockery-type aesthetic to watch components: balance bridges decorated like a French-style garden bed express the quest for visual pleasure characterising the popular scientifi c expressions of the day. Their beauty did not escape commentators at the time, who lauded the clarity of the explanations and the meticulous craftsmanship of the book. A second edition was published in 1761.

The Essai sur l’horlogerie, a work for artists and enthusiasts

The preface of the L’Art de conduire et de régler les pendules et les montres announces the start of the project for Essai sur l’horlogerie, which was completed four years later.

The engraving of the plates of his second work was once again entrusted to Choffard, although the drawings were actually done by Louis-Jacques Goussier. The latter was a mathematician specialising in technical drawings: a large number of illustrations from the Encyclopaedia of Diderot and d’Alembert bear his signature. His contribution doubtless resulted from Ferdinand Berthoud’s own participation in the Encyclopaedia, for which the master horologist wrote – between the late 1750s and the the early 1760s – seven articles including one on “Horology”. This famous text began the Essai sur l’horlogerie with the title “Preliminary discourse”.

The illustrations from the Essai display a higher degree of precision than those from L’Art de conduire et de régler les pendules et les montres. Their sharper lines refl ect the didactic standpoint of the maestro himself, who this time had decided to address a twin readership: namely “Artists” and “Connoisseurs”, meaning professionals on the one hand and individuals capable of observing and judiciously assessing mechanical objects. Ferdinand Berthoud defi ned the latter as “Connoisseurs of Art” or “Connoisseurs of Mechanics”. He was doubtless referring to members of high society with a keen interest in horology, and who also happened to represent a potential clientele.

Counteracting the cult of workshop secrecy

The Essai sur l’horlogerie project went further than that of L’Art de conduire et de régler les pendules et les montres. It drew its strength from the idea of sharing knowledge, which the master horologist reaffi rmed on several occasions. He believed that this sharing, which ran directly counter to the prevailing laws of workshop secrecy, must be done in comprehensible language, as underscored by the use of the title “essay” to distinguish this book from a learned treatise. The chapters composing the two volumes of the Essai sur l’horlogerie correspond to as many lessons that Ferdinand Berthoud might have taught in front of an audience. They skilfully combine theory and practice, concrete examples drawn from experience and principles of execution, designed to enable everyone to understand and fully appreciate the art of horology.

Over the years, this pedagogical mission came to represent one of the specific characteristics of the Berthoud workshop. The founder’s nephew Louis Berthoud clearly recalled this legacy, and in 1812 published Entretiens sur l’horlogerie à l’usage de la marine (Discussions on horology for the Navy) bringing together the horology lessons he had himself taught to several students.