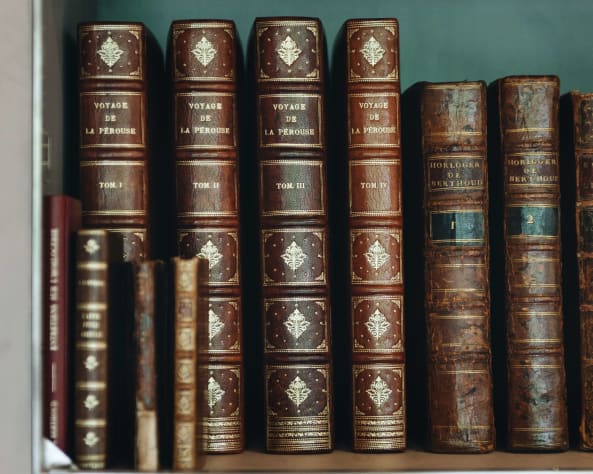

In May 1763, Ferdinand Berthoud was dispatched to London to observe John Harrison’s marine chronometer. He made the most of his stay to campaign for his election to the prestigious Royal Society, of which he became a corresponding member in February 1764.

In the 18th century, craftsmen were barred from the Academy of Sciences in Paris, which wished to maintain an elitist image of knowledge, exempt from any ties with the world of trade and commerce. The episode relating to L’Art de l’horlogerie, the writing of which was finally entrusted to Jean-Baptiste Le Roy, is a perfect example of this standpoint. The latter was not shared by the Royal Society of London for the Improvement of Natural Knowledge, better known as the Royal Society. This English institution created in 1660 was open to deserving artisans, in recognition of their essential contribution to the advancement of technical and scientific knowledge. Becoming one of its members therefore represented a fundamental milestone in Ferdinand Berthoud’s career.

The watchmaker arrived in London May 1st 1763. In mid-April 1763, the Academy had in fact commissioned him to accompany mathematician Charles Etienne Louis Le Camus to England to analyse the longitude chronometer that John Harrison had just made. The pair has 12,000 pounds with them and stayed several weeks in London, where they met the astronomer De Lalande. They waited in vain for Harrison to reveal the secrets of his mechanism and, as we now know, returned to France without having seen the model.

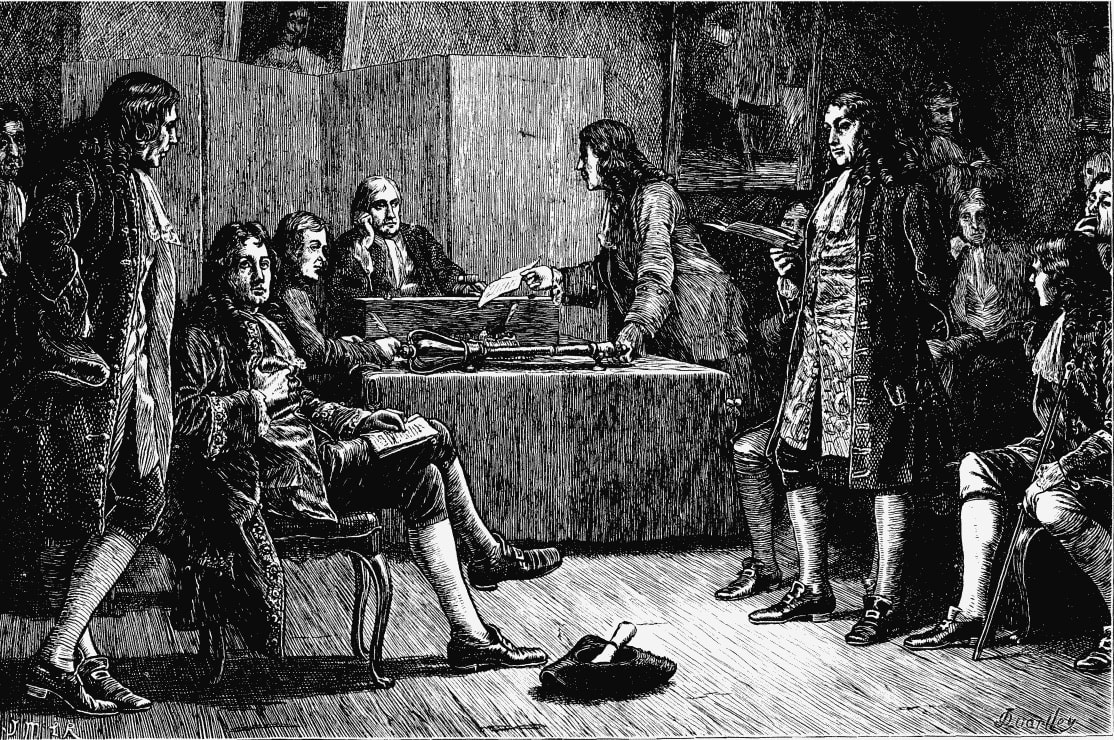

Berthoud nonetheless made the most of his stay in several respects. As a true tourist, he explored the capital, its attractions and its bubbling cultural life. In parallel, he established ties with English scientists. On May 12th 1763, he attended his first ever session of the Royal Society in the company of Le Camus and De Lalande. On this occasion, he donated a copy of his Essai sur l’horlogerie to the venerable institution and returned on June 2nd for another session.

Meanwhile, the Academy of Sciences in Paris wrote a recommendation letter to support his nomination to the Royal Society; its signatories included Abbé Nollet, D’Alembert, La Condamine and Duhamel du Monceau. The same type of letter on behalf of Lalande had been written on March 29th; and the one for Le Camus would be dated June 9th 1763. In accordance with the Society’s admissions procedure, these documents, referred to as “certificates”, were exhibited for several weeks prior to the election to fellowship. These archives include two recommendation letters supporting Berthoud’s nomination: the one from the Academy; and the one sent in October 1763 and written at Berthoud’s personal request by Basle-born mathematician Daniel Bernouilli, himself a member of the Royal Society. They were displayed as of November 10th that same year, and on February 16th 1764, Berthoud was at last approved as a foreign member. The list of new admissions for the year 1764 records his name as “Ferdin. Berthoud, Neocom. Helvetus” [Swiss citizen, from Neuchâtel], thereby emphasising his origins in Neuchâtel and Switzerland.

Nonetheless, his definitive recognition within the academic world was confirmed a year later, when Berthoud himself became a signatory of a recommendation letter sent by the Academy of Sciences, despite not being a member of the latter institution. This was the missive on behalf of Count Hans Moritz von Brühl, ambassador of Saxony to London, renowned for his passion for science. It is dated March 5th 1765 and Berthoud is the only non-member of the academy to have put his name to this document. He was in fact entitled to sign it because of his election to the Royal Society that had established him as an acknowledged scholar.

Images caption

- A Royal Society meeting. Walter Thornbury, “Fleet Street: Northern tributaries (continued)”, in: Old and New London: Volume 1, London, 1878, pp. 92-104.

- A Prospect of the City of London, copper engraving by Johannes Kip, published by J. Smith, London, circa 1720.

- Ferdinand Berthoud, precision regulator table clock with calendar and equation of time, 1764.

- Detail of a 1764 precision regulator table clock with calendar and equation of time by Ferdinand Berthoud.