Throughout his career, Ferdinand Berthoud regularly submitted various memoirs and procedures to the Académie des Sciences. His assiduity testified to his talents and ensured the protection of influential members of this scholarly society. The latter guaranteed him supremacy in the realm of marine chronometry in the mid-1760s, thereby unlocking the gates to success.

In 18th-century Paris, no patent system protecting the intellectual property rights of artisans and inventors yet existed. The Académie des Sciences exercised a virtual monopoly over the field of technical and scientific invention. This meant that the only way of gaining formal recognition for the ingenuity and usefulness of a procedure was to submit it to scholars’ judgement. For each submission, a commission of experts generally composed of three members analysed and approved ideas and objects – in an occasionally arbitrary manner. As Ferdinand Berthoud admitted: “les approbations de l’Académie ne doivent pas toujours servir de fondement pour fixer la bonté d’une machine […]. Ces Messieurs, pour favoriser les progrès des Arts, sont obligés de louer les Artistes.” [the Academy’s approvals must not systematically serve to confirm the fitness for purpose of a machine […]. These gentlemen, in order to foster the progress of the Arts, are obliged to praise the Artists”[1]].

Many procedures submitted to the Academy stem from the watch industry. The race for horological creativity and the development of new escapements became particularly dynamic in the 1750s. Ferdinand Berthoud was very much part of the action. In 1752, he sent a memoir on an equation clock, which probably earned him a request for his cooperation with Diderot and d’Alembert’s Encyclopaedia. The simplicity and ingenuity of the clock are mentioned in the Academy’s official publication, the 1752 volume of the Histoire de l’Académie royale des sciences[2].

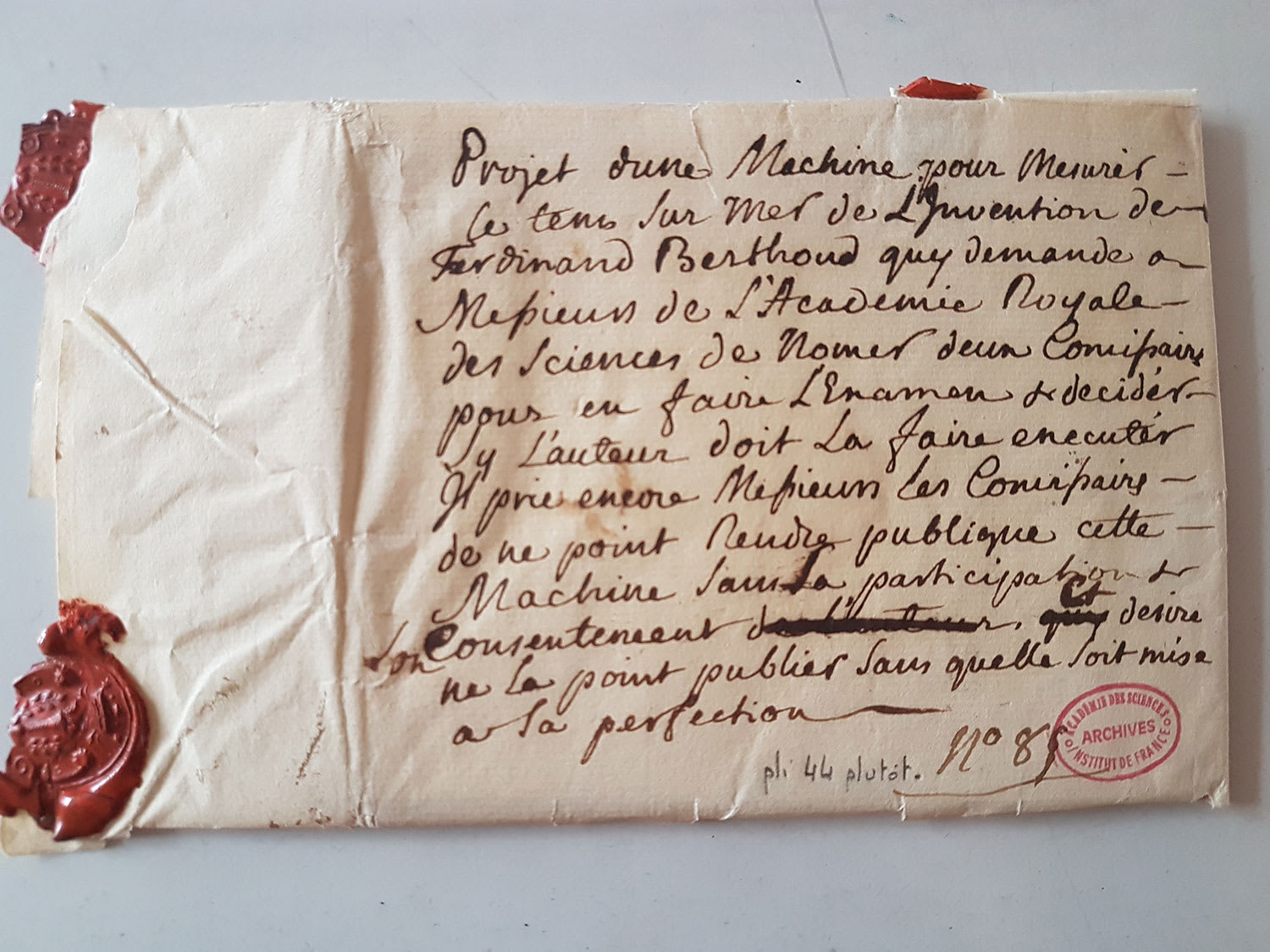

In 1754, having officially become a master watchmaker, Berthoud had another of his equation clocks – as well as watch – approved by the Academy. Moreover, that same year, he submitted a first project for a machine “pour mesurer le temps en mer” [for measuring time at sea] under sealed cover, a procedure serving to protect the date of a discovery. The project testifies to the early involvement in the field of marine chronometry of the watchmaker hailing from the Swiss village of Plancemont near Couvet.

Six years later, he submitted a new description of “principes de construction d’une horloge marine” [construction principles for a marine clock], again under sealed cover. It related to marine clock No 1. At Ferdinand Berthoud’s request, the document (of which a complement was submitted in February 1761) was unsealed upon his return from London in June 1763. The master watchmaker thereby confirmed that, despite the failure of his English mission, his project for a machine preceded John Harrison’s marine watch.

The report by the Academy’s experts, which confirmed Berthoud’s status as a chronometer-maker, was nonetheless not written until one year later, in June 1764. Building on his growing success, Ferdinand Berthoud presented a memoir in August 1764 dealing with the manner of testing his marine clock at sea. In the same text, he announced the creation of three new models, of which he provided a description under sealed cover.

His stay in London indeed appears to have inspired him, since in September 1763 he also submitted the project for a clock equipped with a thermometer – based on the model made by Harrison – along with a memoir on English varnish in September 1764.

During the same period, Pierre Le Roy also submitted to the Academy a project for a marine clock, which did not however appear to elicit much enthusiasm among scholars. By then, it was Ferdinand Berthoud who was in favour among the illustrious gathering. Witness a speech delivered by mathematician Pierre Charles Le Monnier in February 1765 in front of his fellow members, in which he expressed his dream of a French-English maritime mission that would compare Berthoud and Harrison’s marine clocks on the very same ship. As we know, it was not until two years later that the Academy launched its first marine chronometry competition.

Images captions:

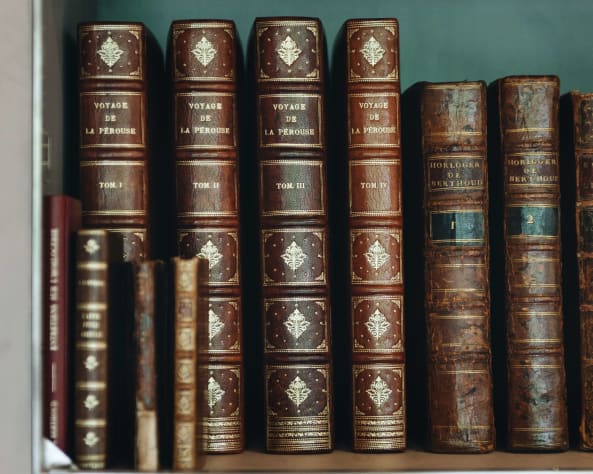

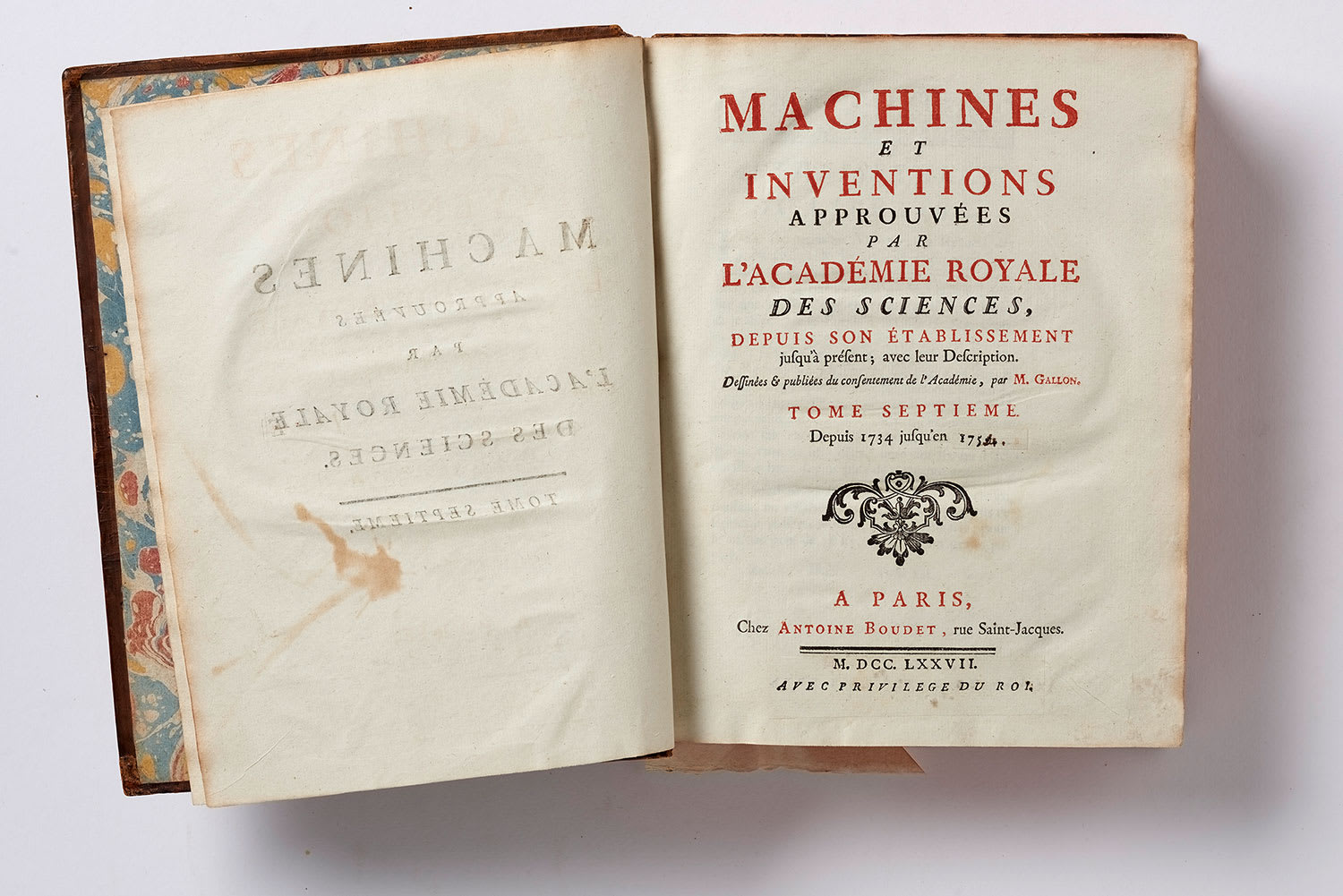

Jean-Gaffin Gallon, Machines et inventions de l’Académie royale des sciences, depuis son établissement jusqu’à présent; avec leur Description, [Machines and inventions of the Royal Academy of Sciences, from its founding to the present day; with their Description], volume VII (from 1734 to 1754), Paris, Antoine Boudet, 1777, page de titre.

Jean-Gaffin Gallon, Machines et inventions de l’Académie royale des sciences, depuis son établissement jusqu’à présent; avec leur Description, [Machines and inventions of the Royal Academy of Sciences, from its founding to the present day; with their Description], volume VII (from 1734 to 1754), Paris, Antoine Boudet, 1777, p. 425.

Ferdinand Berthoud, « Pendule à équation », gravure sur cuivre, par De la Gardette Sculp., in : Jean-Gaffin Gallon, Machines et inventions de l’Académie royale des sciences, depuis son établissement jusqu’à présent; avec leur Description, [Machines and inventions of the Royal Academy of Sciences, from its founding to the present day; with their Description], volume VII (from 1734 to 1754), Paris, Antoine Boudet, 1777, pl. I, pp. 425-428.

Jean-Gaffin Gallon, Machines et inventions de l’Académie royale des sciences, depuis son établissement jusqu’à présent; avec leur Description, [Machines and inventions of the Royal Academy of Sciences, from its founding to the present day; with their Description], volume VII (from 1734 to 1754), Paris, Antoine Boudet, 1777, p. 473.

Ferdinand Berthoud, “Pendule à équation qui va un an sans remonter”, [Equation clock that runs for one year without winding], copperplate engraving by De la Gardette Sculp., in: Jean-Gaffin Gallon, Machines et inventions de l’Académie royale des sciences, depuis son établissement jusqu’à présent ; avec leur Description, [Machines and inventions of the Royal Academy of Sciences, from its founding to the present day; with their Description], volume VII (from 1734 to 1754), Paris, Antoine Boudet, 1777, pl. I, pp. 473-476.

Ferdinand Berthoud, “Pendule à équation qui va un an sans remonter”, [Equation clock that runs for one year without winding], copperplate engraving by De la Gardette Sculp., in: Jean-Gaffin Gallon, Machines et inventions de l’Académie royale des sciences, depuis son établissement jusqu’à présent ; avec leur Description, t. VII [Machines and inventions of the Royal Academy of Sciences, from its founding to the present day; with their Description], volume VII (from 1734 to 1754), Paris, Antoine Boudet, 1777, plate II, pp. 473-476.

Ferdinand Berthoud, “Vue perspective de l’Horloge Marine” [A perspective view of the Marine Clock] in : Essai sur l’horlogerie, dans lequel on traite de cet art relativement à l’usage civil, à l’astronomie et à la navigation, en établissant des principes confirmés par l’expérience, [Essay on horology, in which its civilian use and its applications in astronomy and navigation are examined, while establishing principles confirmed by experiment], volume II, Paris : published by J. Cl. Jombert, Musier et Panckoucke (booksellers), 1763, plate XXX.

[1] Essai sur l’horlogerie, [Essay on Horology], Paris, 1763, vol. 1, p. 207.

[2] Histoire de l’Académie royale des sciences, [History of the Royal Academy of Science], Paris, 1757, p. 147.

Next article

Ferdinand Berthoud's under sealed cover