In one of his “journaux d’expériences” (diaries of experiences), Ferdinand Berthoud consigned an ambitious book project that long remained unknown. It was to be titled L’Art de l’Horlogerie, a richly illustrated folio work comprising several volumes, which several members of the Academy of Sciences apparently wished to entrust him with writing for the famous Description des arts et métiers (Description of arts and crafts) series. Berthoud sketched out the plan early in 1863, but the various volumes were finally not published. The project nonetheless gave him an opportunity to reflect on a new augmented edition of his Essai sur l’horlogerie (Essay on horology). He envisaged this revised version as an encyclopaedic work uniting the sum of his watchmaking expertise and that of his era, which he would bequeath to posterity.

Ferdinand Berthoud, an acknowledged author

The two volumes of the Essai sur l’horlogerie at last arrived in bookstores at the start of 1763; Parisian newspapers mention its publication in mid-January. Nonetheless, at the very time when the work was about to be distributed and become the success we now know, Ferdinand Berthoud already had another book project in mind. On January 1763, he notes in his Journal d’Expériences et de Recherches sur l’horlogerie n. 5, preserved in the archives of the Bibliothèque du Conservatoire des arts et des métiers, Paris, ms. 52 (Library of the Arts and Crafts Conservatory of Paris, ms 52), that several members of the Academy of Sciences envisaged asking him to write a book entitled L’Art de l’Horlogerie, which would become part of the Academy’s prestigious series dedicated to artisanal expertise and named Description des arts et métiers.

Description des arts et métiers

Since its founding 1675, the Academy of Sciences had been invited by Colbert to study the machines, tools and procedures required to produce descriptions of various professions. In concrete terms, the plan to print a collection had first been conducted by the physicists and naturalist René-Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur (1683-1757), known for his studies on insects and his thermometric scale. But it was essentially with the agronomist Duhamel du Monceau (1700-1782), who was appointed to direct the collection on Réamur’s death, that the series enjoyed a real boom in the 1760s. Duhamel himself wrote a first tome titled L’Art du Charbonnier (Art of the Coalmaker) published in 1760, Seven other arts were covered in the space of three years, including L’Art de faire le parchemin (The Art of Parchment Making) in 1761, followed in 1762 by L’Art de travailler les cuirs dorés ou argentés (The Art of Crafting Gilt or Silvered Leathers), L’Art du cartonnier (The Art of the Cardboard Craftsman) L’Art du cirier (The Art of the Wax Maker) and L’Art du cartier (The Art of the Card Maker). These volumes which the Academy produced in conjunction with various printers and bookstore owners, are large, costly and abundantly illustrated folio books; the vast majority of their authorities were members of the scholarly institution. The publication of the series continued at a rapid pace until the 1780s, when it ceased: in all, it comprised 75 descriptions spread between more than 30 volumes (ill. 1). The Société typographique de Neuchâtel produced quarto counterfeit copies between the 1770s and the early 1780s.

An authentic encyclopaedia of horology, the watchmaking art for posterity

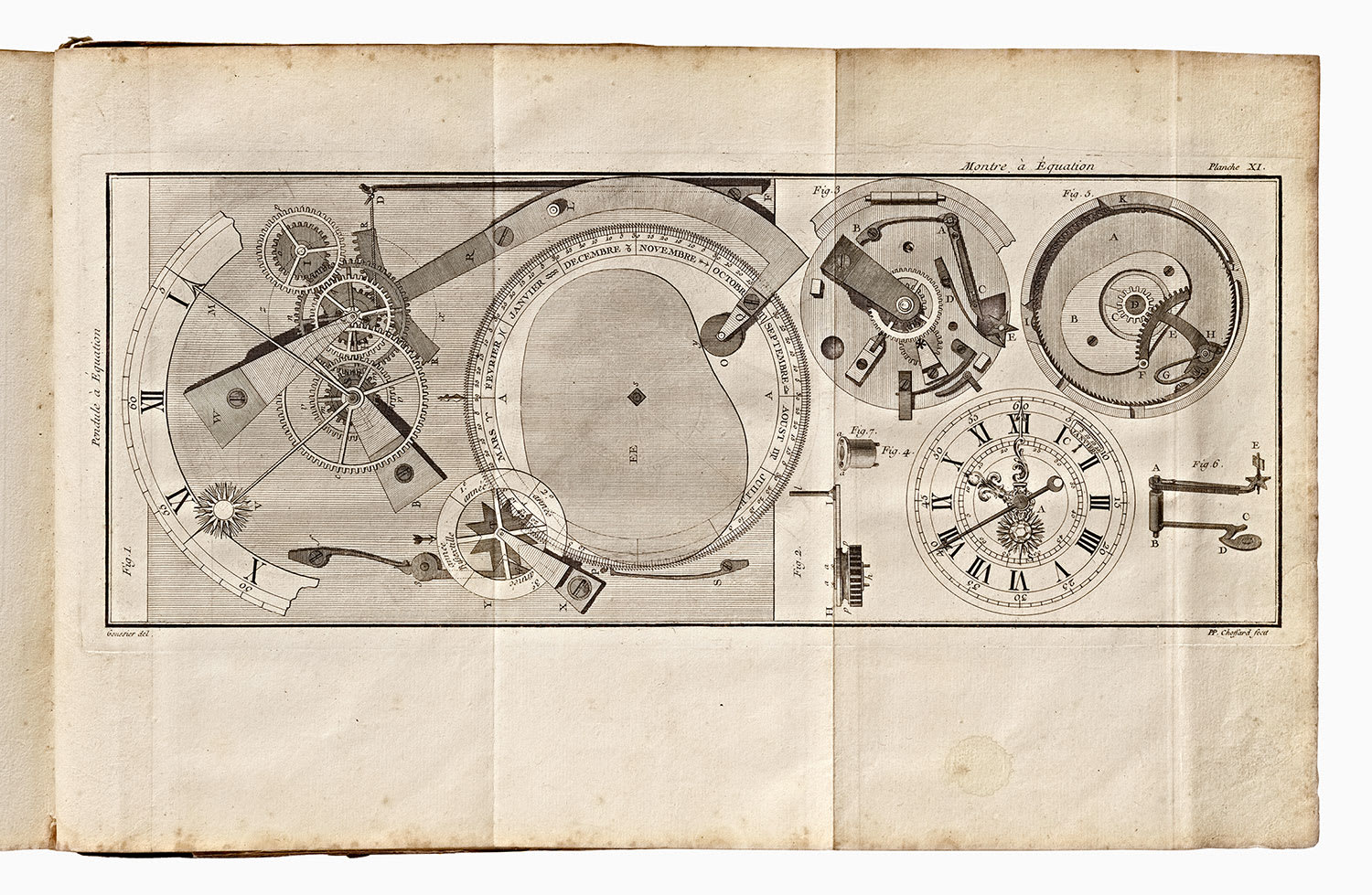

It was thus with a sizeable endeavour with which several scientists, whose names are unfortunately not known to us, desired to associate Berthoud. His reputation as an author and horologist was thus recognised by the Academy itself. The watchmaker was naturally delighted at the idea of participating in the Description des arts et métiers. As his writes in his journal: “Mon travail pourra avoir place parmi ce que donnent les illustres académiciens”, (“My work will find its place among contributions from illustrious members of the Academy”). Berthoud thus begin developing the plan of a book representing a considerably enriched updating of his Essai sur l’horlogerie and bearing a very long title (ill 2): L’Art de l’Horlogerie, traité dans toute son étendue soit relativement à l’usage civil, à l’astronomie ou à la navigation et suivant des principes confirmés par l’expérience, ou entrés dans tous les détails de construction des machines d’horlogerie, leur description et un traité complet de la main d’œuvre de toutes les parties de cet art (The Art of Horology, dealt with in full, in which its civilian use and its applications in astronomy and navigation are examined, while establishing principles confirmed by experiment, or entering into all details of construction of watchmaking machines, their description and a complete treatise of the workmanship involved in all areas of this art). This title as well as the abundant table of contents correspond to clear-cut encyclopaedic ambitions. Berthoud clearly aims to prepare a work gathering all the horological expertise of his era, in order to bequeath it to posterity, in case “il arrivait que des siècles de barbarie nuisissent à ensevelir nos arts” (it should occur that centuries of barbarianism should succeed in burying our arts”). It was thus to be an imposing work spread between 12 volumes and taking account of machines, components, tools and procedures: it would neglect no aspect of horological production. This naturally implied a splendid and accurate iconographic set-up, similar to that used for his Essai sur l’horlogerie (ill. 3); as a wealthy artisan, he was prepared to cover the costs of producing the plates which he saw as a necessary instrument “pour faire entendre un art difficile et susceptible d’une extrême délicatesse d’exécution” (to promote an understanding of a difficult art involving such delicate execution) as that of watchmaking.

A conflict of authority

Berthoud was however not the only candidate for the writing of a L’Art de l’Horlogerie, which was obviously a highly significant project for the Academy. The astronomer and Academy member Joseph Jerôme Lefrançois de Lalande (1732-1807), who had already written about several arts for the Description des arts et des métiers between 1761 and 1762, also wished to be entrusted with these volumes. When Berthoud wrote a letter to the Academy in January 1763, once again manifesting his interest in the project, the two men sought to come to an understanding that in the end proved pointless. In the end, the Academy of Sciences chose a third author: the geometer Jean-Baptiste Leroy (1720-1800), associate member of the institution and, more importantly the son of Julien Leroy. However, Jean-Baptiste did not complete the mission entrusted to him by the Academy, thereby depriving the Description des art et métiers of a text that should have been one of the most important in the collection.

The failure of the project for L’Art de l’Horlogerie did not prove damaging to Ferdinand Berthoud’s career. We know that several months later, he was sent to England with the mathematician Charles-Etienne Louis Camus (1699-1768) to analyse John Harrison’s marine chronometer. Nonetheless, the quarrels surrounding the writing of the work remind us of the difficulties experienced in France by the custodians of knowledge and expertise considered as more manual than intellectual; as well as a reflection of the overwhelming influence wielded by powerful institutions such as the Academy of Sciences on technological knowledge during the Age of Enlightenment.

Images caption

- Henri-Louis Duhamel Du Monceau, “Art du charbonnier ou Manière de faire le charbon de bois” (Art of the Coal Maker or the manner of making coal”, in : Description des arts et métiers par l’Académie royale des sciences (Description of Arts and Crafts by the Royal Academy of Sciences), Paris : Desaint et Saillant, 1761, title page. Bibliothèque nationale de France (French National Library)

- Ferdinand Berthoud, Journal d’Expériences et de Recherches sur l’horlogerie n. 5. (Diary of Experiments and Research on Horology no. 5). Bibliothèque du Conservatoire des arts et des métiers, (Library of the Arts and Crafts Conservatory), Paris, ms. 52. Ferdinand Berthoud, L’art de l’horlogerie, traité dans toute son étendue, soit relativement à l’usage civil, à l’astronomie ou à la navigation et suivant des principes confirmés par l’expérience, ou entrés dans tous les détails de construction des machines d’horlogerie, leur description et un traité complet de la main-d’œuvre de toutes les parties de cet art (Dealt with in full, in which its civilian use and its applications in astronomy and navigation are examined, while establishing principles confirmed by experimentation, while entering into all details of construction of watchmaking machines, their description and a complete treatise of the workmanship involved in all areas of this art), non-completed book project, 1763.

- Ferdinand Berthoud, Essai sur l’horlogerie, dans lequel on traite de cet art relativement à l’usage civil, à l’astronomie et à la navigation, en établissant des principes confirmés par l’expérience (Essay on horology, in which its civilian use and its applications in astronomy and navigation are examined, while establishing principles confirmed by experiment), Paris, published by J. Cl. Jombert, Musier et Panckoucke (booksellers), 1763, first volume, plate XI.

- Ferdinand Berthoud, gold quarter repeating à toc watch, No. 2204, circa 1780.