The plan for a “Horological Academy” devised by Ferdinand Berthoud was strongly inspired by the Society of Arts. Uniting both artisans and scientists, the latter had dared to challenge the power of the Academy of Sciences in the realm of technical expertise.

As Ferdinand Berthoud admitted, the model on which he based his “Horological Academy” project was the Society of Arts, an institution that had become a legend in Parisian artisanal circles of the 1760s.[1] Probably founded under the impetus of English clockmaker Henry Sully and placed under the patronage of the young Count of Clermont, its existence was nonetheless short-lived, since its activities lasted from 1726 to the mid-1730s. It had around a hundred members, including associates of the Academy of Sciences. Unlike the latter, the Society of Arts encompassed actual exponents of various trades and professions (watchmakers, enamellers, goldsmiths, sculptors, physicians, etc.) as well as scholars (mathematicians, astronomers, physicists, etc.). It even included manufacturers, which was exceptional at the time.

The purpose of this assembly truly unique in its kind was to establish a dialogue between theory and practice, or even to unite them: developing scientific expertise in a pragmatic way in order to contribute to the advancement of knowledge – particularly of the technical variety. The Society of Arts thus provided artisans with a more democratic forum than that represented by the Academy of Sciences, which on principle excluded both practitioners and manufacturers. The Count of Clermont funded the awarding of two prizes per year in the shape of two medals each worth 300 pounds. The organisation also provided an appraisal service, which involved having machines and instruments examined at its own expense. This task, as we have previously seen, was generally undertaken by the scholars of the Academy of Sciences. The pressure exercised by the Academy, of which several members were unhappy about the competition from the Society of Arts, is doubtless one of the causes behind the latter’s swift decline.

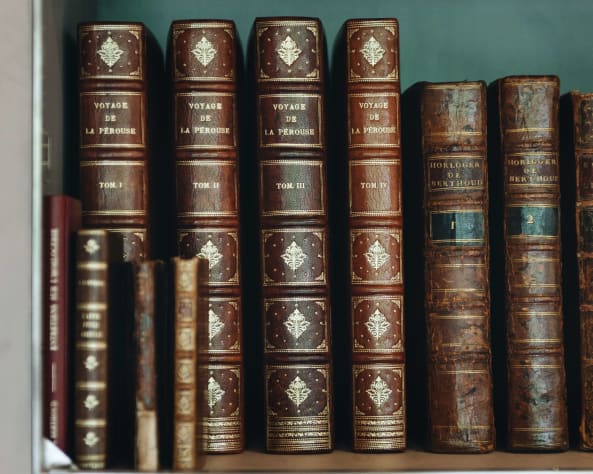

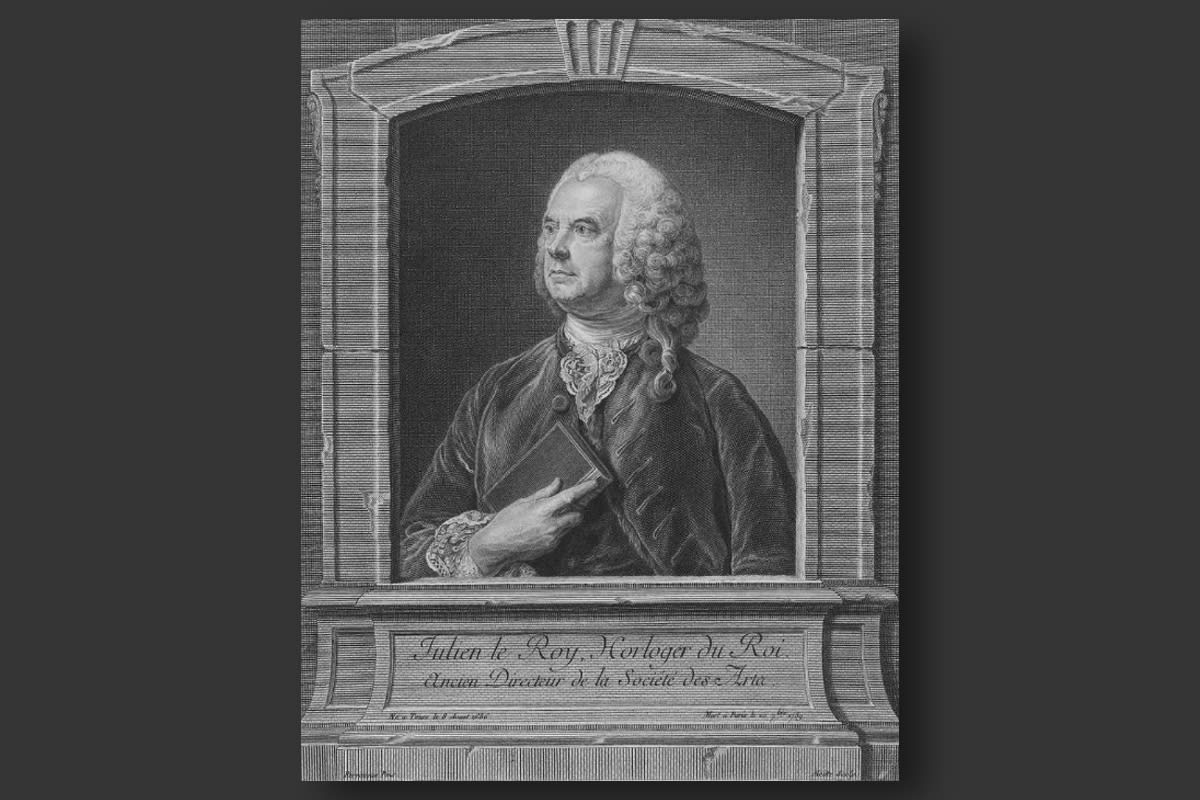

It is thus hardly surprising that the Society of Arts was a source of fascination both for Ferdinand Berthoud and more generally for the world of horology of the time. Horologists indeed played a prominent role within the Society. While Sully was one of the founders, Julien Le Roy chaired it for several years and his son Pierre was among the members, as were Basel-based clockmaker Enderlin; the Duke of Orleans’ watchmaker Pierre Gaudron; along with Jean-Baptiste Dutertre and Andrieu, who served as a lawyer of the Parisian Corporation of Watchmakers.

The “Horological Academy” could thus be said to have embodied hope for the rebirth of the Society of Arts, as well as of the egalitarian and scientific values it embodied. According to Berthoud, several of his colleagues and “intelligent artists” were prepared, from the 1750s onwards, to strive towards bringing this monumental project to fruition. He notably mentioned Julien Le Roy and Antoine Thiout[2]. Nonetheless, the project foundered due to personal conflicts between certain master-watchmakers, and Berthoud provided no explanations in this respect.

All that remains for us to do is speculate on the potential destiny of this “Horological Academy” if it had seen the light of day. It would probably have represented a key moment in the history of 18th century watchmaking, of which – like Berthoud himself – we can now only dream.

List of illustrations

1) Ferdinand Berthoud, Essai sur l’horlogerie, dans lequel on traite de cet art relativement à l’usage civil, à l’astronomie et à la navigation, en établissant des principes confirmés par l’expérience, [Essay on horology, in which its civilian use and its applications in astronomy and navigation are examined, while establishing principles confirmed by experiment], Paris : chez J. Cl. Jombert, Musier et Panckoucke (booksellers), 1763, pl. XVII.

2) Ferdinand Berthoud, Essai sur l’horlogerie, dans lequel on traite de cet art relativement à l’usage civil, à l’astronomie et à la navigation, en établissant des principes confirmés par l’expérience, [Essay on horology, in which its civilian use and its applications in astronomy and navigation are examined, while establishing principles confirmed by experiment], Paris : chez J. Cl. Jombert, Musier et Panckoucke (booksellers), 1763, pl. XVIII.

3) Ferdinand Berthoud, Essai sur l’horlogerie, dans lequel on traite de cet art relativement à l’usage civil, à l’astronomie et à la navigation, en établissant des principes confirmés par l’expérience, [Essay on horology, in which its civilian use and its applications in astronomy and navigation are examined, while establishing principles confirmed by experiment], Paris : chez J. Cl. Jombert, Musier et Panckoucke (booksellers), 1763, pl. XIX.

4) Louis-Jean Desprez, Vue imaginaire de l’Ecole des Ponts et Chaussées, [Imaginary View of the School of Bridges and Highways], ink drawing, circa 1770-1780. Musée Carnavalet, Paris.

[1] Ferdinand Berthoud, Discours préliminaire sur l’horlogerie [Preliminary Discourse on Horology] in: Essai sur l’horlogerie [Essay on Horology], 1763, vol. 1, p. xix.

[2] Ferdinand Berthoud, Essai sur l’horlogerie, [Essay on Horology], vol. 1, p. xlvij