In 1770, just ten years after completing his first navigational timekeeping instrument, Ferdinand Berthoud received the "Brevet d'Horloger Méchanicien du Roi & de la Marine, ayant l'inspection de la construction des Horloges Marines" [Patent Royal as Master Clockmaker-mechanic by appointment to the King & Navy, in charge of supervising the construction of marine chronometers]. This distinction, followed by an important commission from His Majesty Louis XV, confirmed his vocation and enabled him to devote himself fully to the pursuit of this calling.

Tracking East-West position on the high seas

The means of determining longitudes at sea was one of the most exciting 18th century debates. Faced with sometimes empirical navigation methods that resulted in considerable losses of ships, precious human lives and rich cargoes, it became imperative to create accurate maritime charts. The governments of the most powerful European nations, such as France and Great Britain, invested in exploratory expeditions across the oceans. Elite astronomers, cartographers, hydrographers, naturalists and other scientists boarded ships equipped with state-of-the-art measuring instruments.

“Le Problème des longitudes en mer se réduit à ceci : Déterminer, à un même instant, l’heure du vaisseau et l’heure du méridien de départ, ou de tout autre méridien convenu. La différence des heures réduites en partie de l’équateur (à raison de quinze degrés pour une heure, et d’un degré pour quatre minutes de temps, &c.) donne la longitude du navire rapportée au méridien qu’on a choisi pour terme de comparaison.”[1] [The Longitude at Sea problem comes down to this: How to determine, at the same precise moment, the time aboard the ship and the time at the departure meridian, or any other agreed meridian. The difference in hours calculated as gradually dwindling from the equator (at a rate of fifteen degrees for one hour, and one degree for four minutes of time, &c.) gives the longitude of the ship relative to the meridian chosen for comparison purposes.] Longitude clocks would enable this calculation whatever the weather conditions, whereas until then heavenly bodies had been the sole points of reference on the open sea.

Researching, developing, creating, fine-tuning and sharing

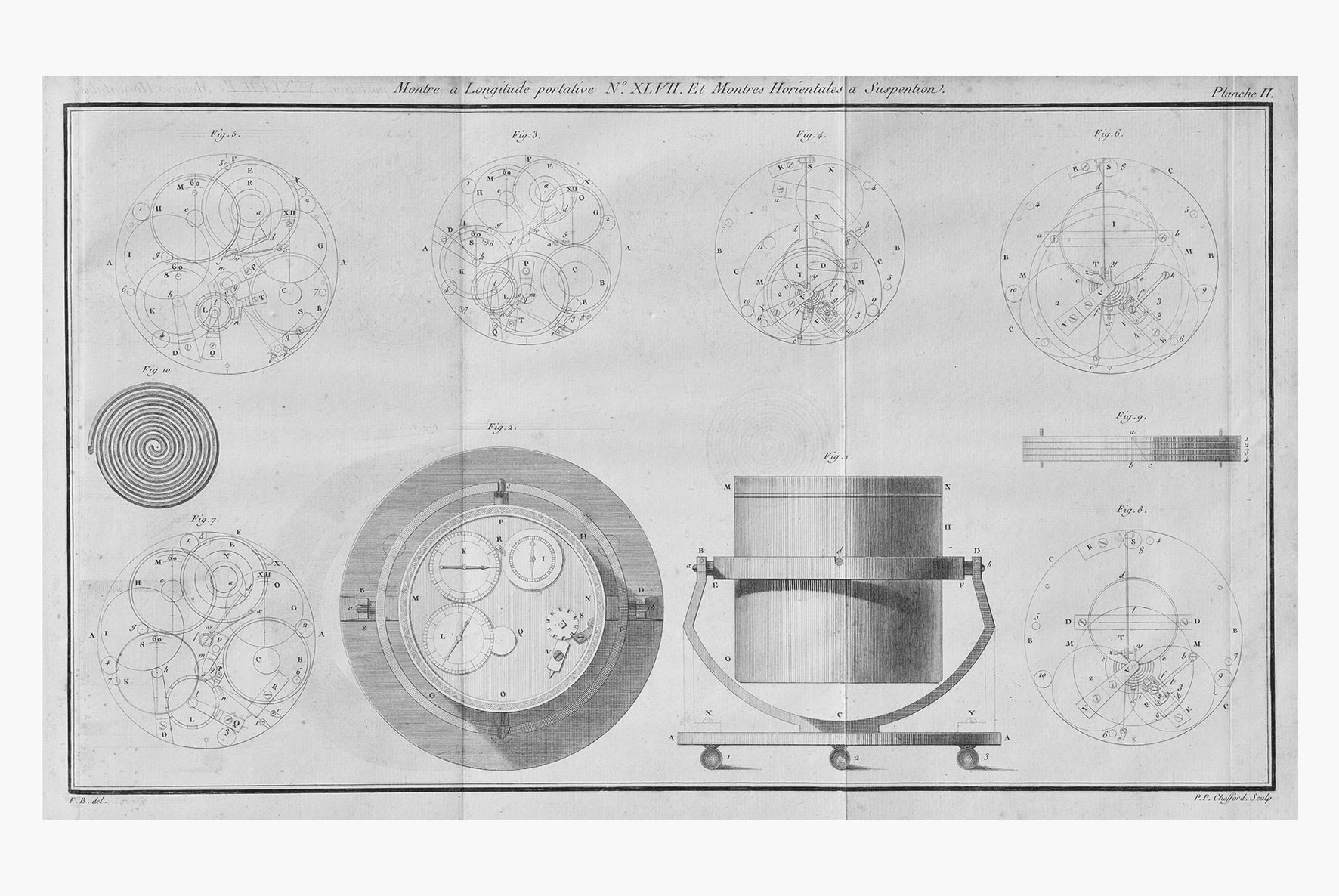

By carefully studying the work of his predecessors and contemporaries, Ferdinand Berthoud took up the challenge of building a first marine chronometer, which he finalised in 1760 and of which he published the full description three years later in his Essai sur l'horlogerie [Essay on Horology]. From then on, and throughout his life, he never ceased to improve this instrument in order to refine its precision and reinforce its reliability. Gradually reducing its volume and weight, the watchmaker alternated between spring-driven mechanisms equipped with a fusee, and alternative weight-driven versions, while experimenting with ways to cancel out the consequences of temperature differences. In the course of his books and articles, Berthoud presented the evolution of his work in minute detail, under the names of marine clock, marine watch, longitude clock or longitude watch.

“N.° XXX Horl : a Longit par Ferdinand Berthoud”

(engraved on the mainplate bearing the dials)

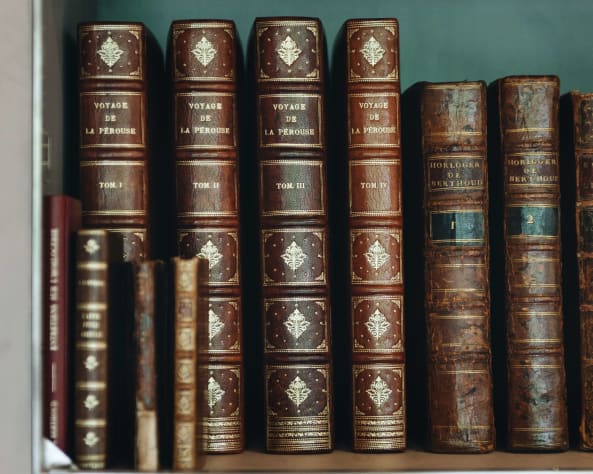

Preserved in the L.U.CEUM collections, the longitude clock N° XXX is the only one of a series of five made between 1778 and 1782[2] that has survived intact, along with its original walnut case. Among these timepieces, two were lost at sea in 1788 during the scientific expedition led by Jean-François de Galaup, Count of La Pérouse.

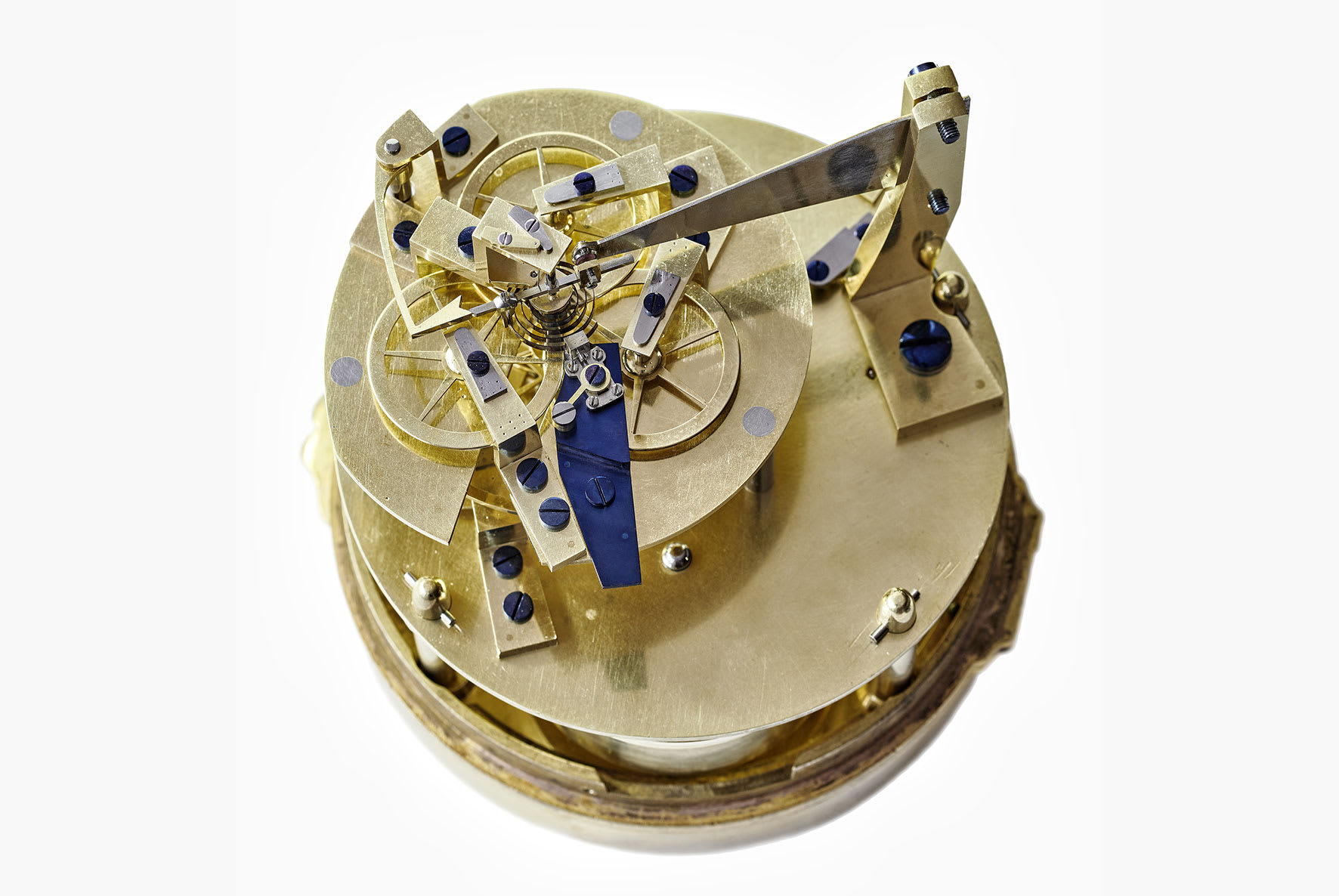

Like the Marine Watch No. 6, 1777 (L.U.CEUM) featuring a mechanism equipped with a compensating gridiron, the diminutively sized longitude clock No. XXX, equipped with a bimetallic steel and brass attachment, testifies to Ferdinand Berthoud's constant quest for precision.

List of illustrations

1) Ferdinand Berthoud, longitude clock No XXX, circa 1780, overall view (L.U.CEUM collection, Fleurier). Case dimensions: Height 22.7 cm, Width 25.7 x 25.7 cm.

2) Ferdinand Berthoud, longitude clock No XXX, circa 1780, view of the clock and gimbal suspension outside their case.

3) Ferdinand Berthoud, longitude clock N° XXX, circa 1780, view of the mechanism, elevation on the fusee side, and of its triangular-shaped bimetallic attachment.

4) Ferdinand Berthoud, longitude clock N° XXX, circa 1780, view of the small plate topped by the bimetallic attachment.

5) Longitude watch N° XLVII depicted on this plate (excerpt from Ferdinand Berthoud’s work Traité des Montres à Longitudes [Treatise on Longitude Watches], Ph.-D. Pierres, Paris, 1792, plate II) showing an evolved version of longitude clock N° XXX.

[1] Histoire de la mesure du temps par les horloges, [The history of time measurement with clocks], Paris, Imprimerie de la République, Year X (1802), volume two, chapter VIII, pages 323 and 324.

[2] In Ferdinand Berthoud, 1727-1807 : Horloger Mécanicien du Roi et de la Marine, directed by Catherine Cardinal, Musée international d’horlogerie, La Chaux-de-Fonds, 1984, page 209.

Next article

The vertical longitude watch