Ferdinand Berthoud is credited with seven articles in Diderot and d’Alembert’s Encylopaedia. Nonetheless, his contribution was probably more substantial. The maestro probably wrote more articles, as well as providing several plates that he had specially made at his own expense for the Essai sur l’horlogerie [Essay on horology].

The Encyclopaedia project spanned two decades and endured numerous stops and starts. Notably criticised by religious circles, the Encyclopaedia was prohibited in 1759, at a time when the volumes of text had reached only the letter ‘G’ and the plates had not yet been published. Printing finally resumed in 1756. Ferdinand Berthoud’s articles entitled “HorlogER”[1] [Horologist] and “HorlogerIE”[2] [Horology], “Pendule en tant qu’appliqué aux horloges (Horlogerie)”[3] [The pendulum as applied to clocks] “and Répétition (Horlogerie)”[4] [Repeating mechanisms in watchmaking] thus appeared only at that time.

In actual fact, Berthoud’s texts were ready at the end of the previous decade. By the time his work L’art de conduire et de régler les montres et les pendules [The art of operating and adjusting watches and clocks] was published in 1759, his cooperation with the Encyclopaedia was already known and lauded by the Parisian press. His articles were distinguished by their clarity, their precision and the elegance of their style. They were full-fledged academic papers. In compliance with the format of the 18th century dictionary, they often comprised a historical introduction, even when dealing with tools. By way of example, one might mention the article by Ferdinand Berthoud titled “Fusée (Machine à tailler les)”[5] [ Fusee (Fusee-cutting machine)]. It provides a better explanation of the operation and purpose of this component inside a mechanism than does its counterpart “Fusee (Horlogerie)”[6], written by Jean-Baptiste Le Roy. Moreover, Berthoud never forgets to complement his explanations with concrete examples, thereby helping readers to gain a better grasp of the procedures he describes. The maestro clearly excelled in the art of popularising his knowledge.

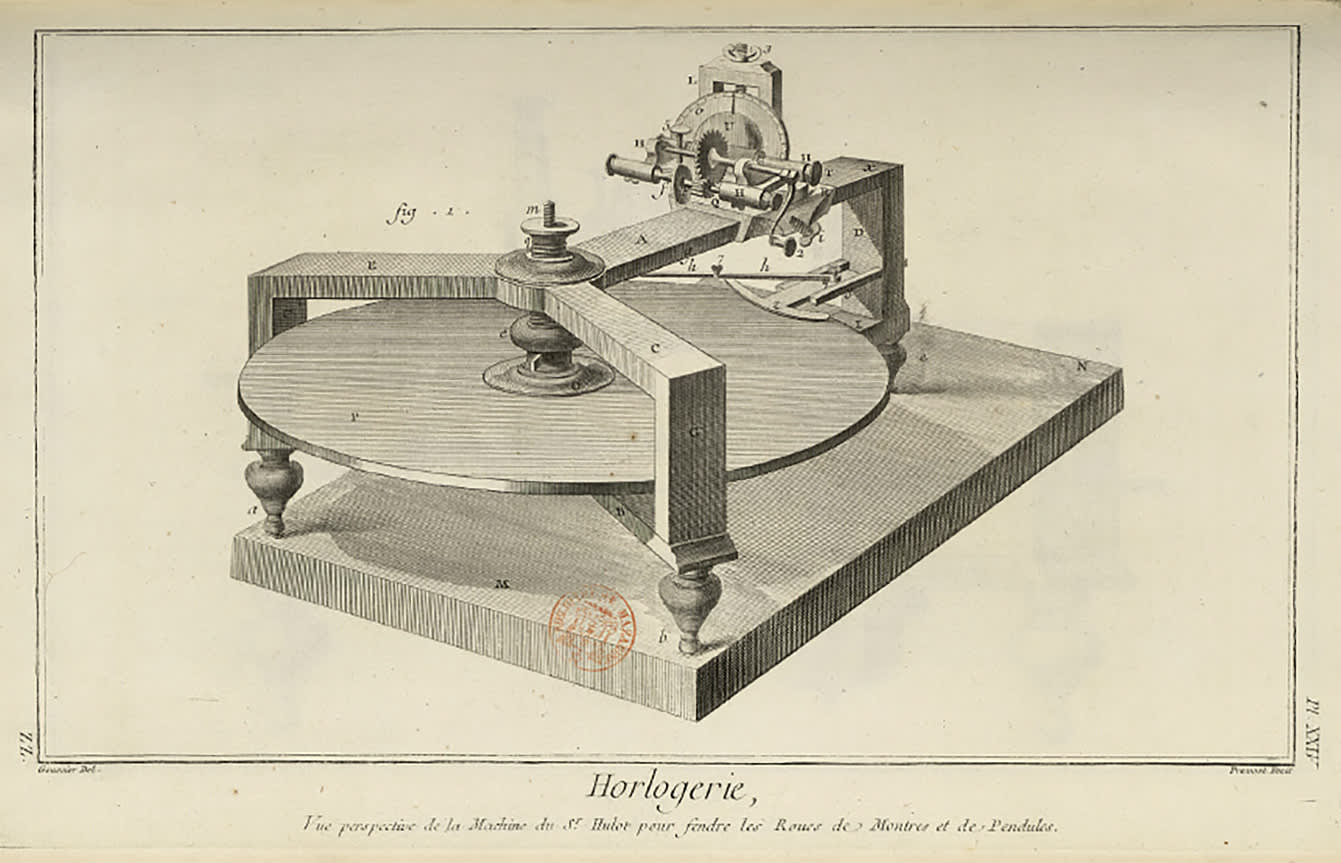

The number of articles officially authored by Berthoud – seven in all – may seem modest compared with the quantity supplied by other writers, Nonetheless, their content and the multiple references they comprise hint at the distinct possibility that the Neuchâtel-born watchmaker’s participation in the Encylopaedia may have been more substantial than it might seem. By way of example, the article “Fendre (Machine à)”[7] [Gear-wheel slotting machine] mentions a text dealing with the “Machine à fendre toutes sortes de nombres” [All kinds of gear-wheel slotting machines] that does not appear in the encyclopaedic dictionary. This reference enables us to deduce that Berthoud had in fact planned a small series of articles on various gear-wheel slotting machines. This means that he should probably be credited with the short article Fendre (machine à) Fendre les roues de montres arbrées [8] [Gear-wheel slotting machine for shafted watch wheels]. Moreover, the latter announces an entry referring to “Machine à fendre les roues de rencontre” [Crown-wheel slotting machine] which was also not published. The reasons why these texts had been cast aside are unfortunately not known. Ferdinand Berthoud also contributed to the fourth volume of plates by providing a number of engravings originally produced for the Essai sur l’horlogerie [Essay on horology], printed two years earlier.

Based on these discoveries, it would be tempting to attribute other articles to Ferdinand Berthoud. The entries “Montre à secondes”[9] [Seconds watches], “Rosette dans les montres” (Horlogerie)[10] [Rosettes in watches (Horology)], and “Pignon, terme de Méchanique” [11] [Pinion, a mechanical term], to mention but a few, are strongly reminiscent of the style of articles written by the master watchmaker. In the absence of sources and proof, we will for now content ourselves with raising the hypothesis, while considering the scope of Berthoud’s cooperation with one of the greatest works of the 18th century.

CAPTIONS

1) Horlogerie, Montre à roue de rencontre, [Horology, watch with crown wheel], plate X, first suite, BB side, drawn by Jacques-Louis Goussier, burin-engraved by Robert Bernard, in: “Recueil de planches, sur les sciences, les arts libéraux, et les arts méchaniques, avec leur explication” [Compendium of plates on the sciences, liberal arts, mechanical arts, complete with their explanation], Paris: Briasson, David, Le Breton, vol. 4, 1765.

2) Horlogerie, Montre à réveil et montre à équation, à secondes concentriques, marquant les Mois et leurs Quantièmes [Horology, alarm watch and equation of time watch, with concentric seconds, marking the months and the dates], plate X, third suite, DD side, drawn by Jacques-Louis Goussier, burin-engraved by Robert Bernard, in : “Recueil de planches, sur les sciences, les arts libéraux, et les arts méchaniques, avec leur explication” [Compendium of plates on the sciences, liberal arts, mechanical arts, complete with their explanation], Paris: Briasson, David, Le Breton, vol. 4, 1765.

3) Vue perspective de la machine du Sr. Hulot pour fendre les Roues de Montres et de Pendules [Perspective view of Mr Hulot’s machine for splitting the gear-wheels of watches and clocks], plate XXIV, side ZZ, drawn by Louis-Jacques Goussier and engraved by Bonaventure-Louis Prévost, in: “Recueil de planches, sur les sciences, les arts libéraux, et les arts méchaniques, avec leur explication” [Compendium of plates on the sciences, liberal arts, mechanical arts, complete with their explanation], Paris: Briasson, David, Le Breton, vol. 4, 1765.

[1] Vol. VIII, 1765, p. 302.

[2] Vol. VIII, 1765, p. 303.

[3] Vol. XII, 1765, p. 298.

[4] Vol. XIV, 1765, p. 133.

[5] Vol. VII, 1757, p. 393.

[6] Vol. VII, 1757, p. 391.

[7] Vol. VI, 1756, p. 482.

[8] Vol. VI, 1756, p. 490.

[9] Vol. X, 1765, p. 691.

[10] Vol. XIV, 1765, p. 370.

[11] Vol. XII, 1765, p. 615.