Ferdinand Berthoud’s visionary spirit found expression through his legacy of watchmaking masterpieces. Nonetheless, the maestro also passed down other projects testifying to his boldness, including the idea of creating a horological Academy.

According to the explanations provided by Ferdinand Berthoud in his Discours préliminaire sur l’Horlogerie[1] [Preliminary Discourse on Horology], watchmakers fall into three categories. The first and largest one is that of mediocre workers striving only to earn money. Lacking any special predispositions or talents, they exercise their profession with no passion. Secondly, there are watchmakers wishing to stand out in the community and seeking to acquire the skills required to be recognised as artists, yet devoid of any innate abilities.

Those belonging to the third category, referred to Berthoud as “intelligent Artists”, represent the horological elite: they apply their natural virtuosity and their taste for art and for horological expertise to showcasing its excellence.

Fine Watchmaking is thus the exclusive preserve of these chosen few endowed with a singular gift, which they nurture by dint of experience, practice and an analytical mindset. For, as Berthoud wrote, “an Artist as I see him does nothing of which he does not feel the effects”.

Nonetheless, the Neuchâtel-born watchmaker admitted that the favourable predispositions of this limited number of masters cannot alone guarantee the perfection of the watchmaking art. He believed that achieving perfection called for healthy emulation and even antagonism.

Ferdinand Berthoud therefore launched the ambitious idea of founding a “Horological Society or Academy” enjoying royal protection. The boldness of the project deserves to be highlighted: no institution of the kind existed at the time in France, nor indeed elsewhere. The details of a project that unfortunately never came to fruition appear in the last pages of the “Preliminary Discourse” of the Essai sur l’horlogerie [Essay on Horology]. Berthoud does not confine himself to providing an organisation chart of the institution, but instead presents the various benefits it would entail, beginning with economic privileges. By motivating artists to aim for continuous improvement and rewarding their efforts by prizes, the Academy would thus reaffirm the supremacy of French horology in the face of English competition. While acknowledging that watchmaking was a fundamental issue at stake on the international market, Berthoud wrote: “it is by establishing an academic Society that the Art of Horology will be able to gain foreign trust”[2].

Berthoud also insists on the pedagogical mission of the organisation. Its members would be examples for young watchmakers, on both technical and moral levels. The “Horological Academy” would thus defend an ethical vision of the watchmaking art, in order to free it from the baseness of commerce and profit that were causing its ruin.

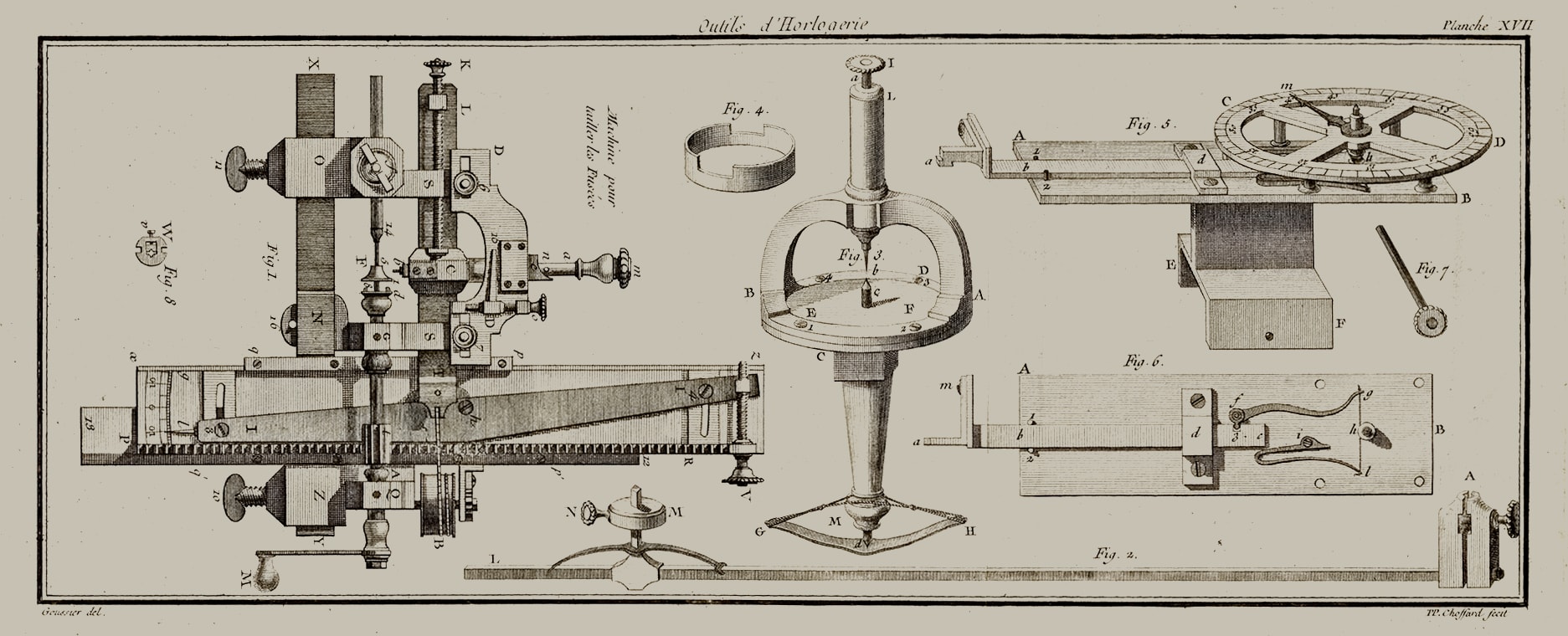

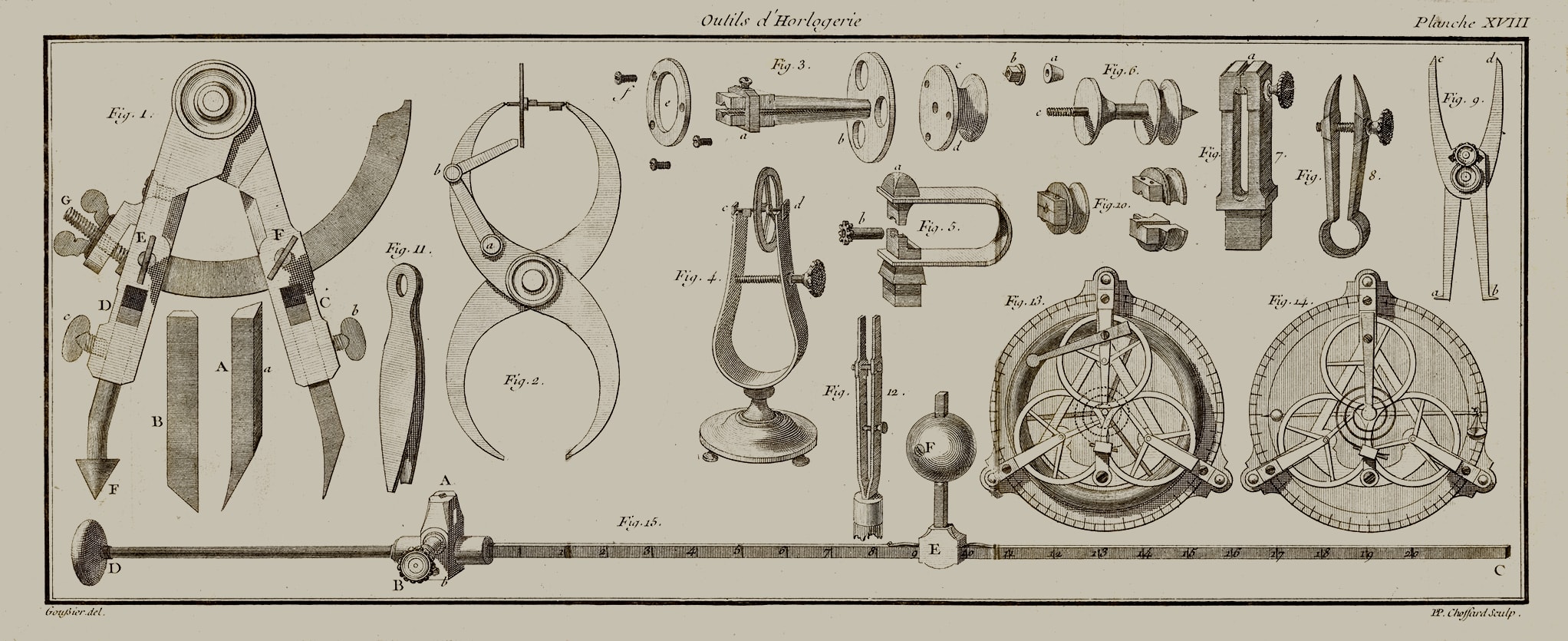

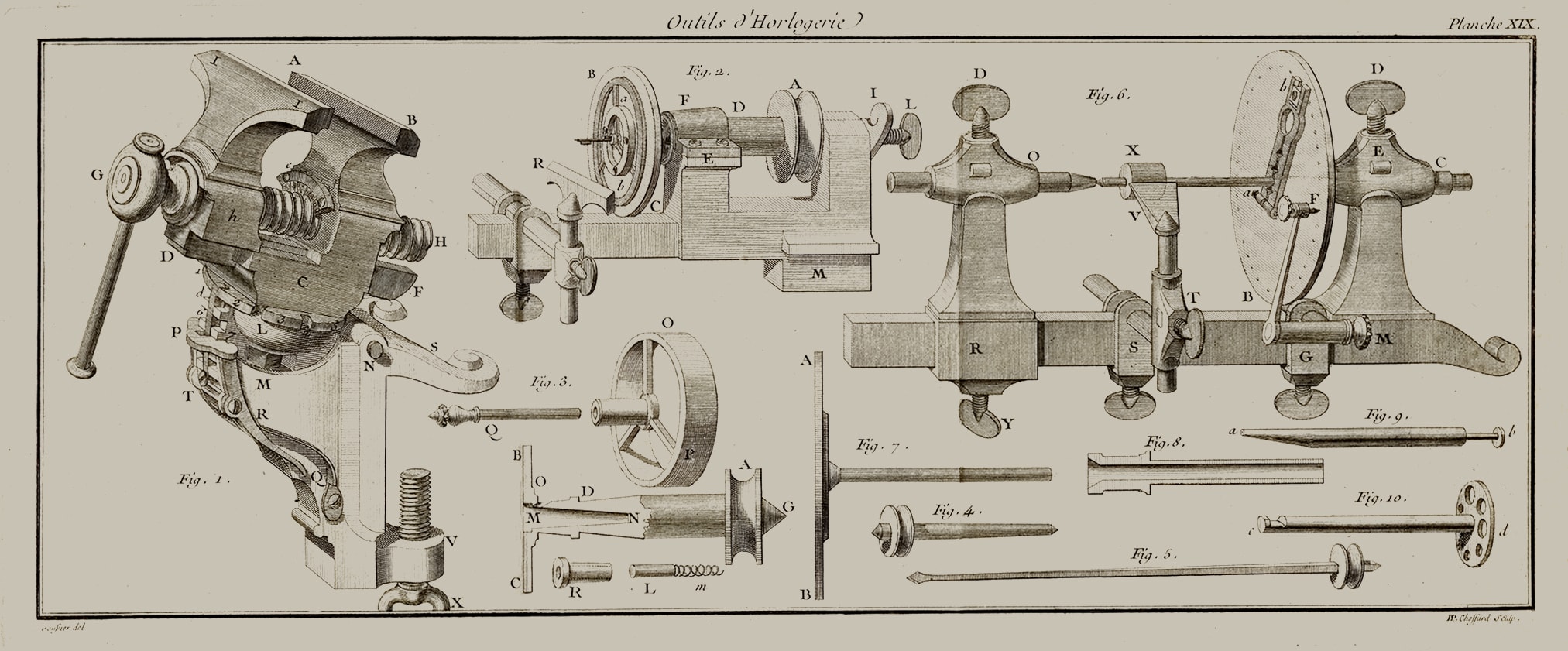

Lastly, we should point out an authentic masterstroke: the importance Ferdinand Berthoud devoted to documents emanating from the proposed Academy. He suggested using its registers – containing discussions, memoirs and images illustrating movements, procedures and tools – that would thus serve as freely available public archives of the watchmaking art. Like patents, these documents would be an essential instrument in safeguarding the inventions and rights of their creators in order to avoid plagiarism.

This perspicacious approach to imagining a “Horological Academy” thereby laid the foundations for the reform of Parisian watchmaking, several decades before the creation of the institutions that are now an integral part of the watchmaking universe.

List of illustrations

1) Ferdinand Berthoud, Essai sur l’horlogerie, dans lequel on traite de cet art relativement à l’usage civil, à l’astronomie et à la navigation, en établissant des principes confirmés par l’expérience, [Essay on horology, in which its civilian use and its applications in astronomy and navigation are examined, while establishing principles confirmed by experiment], Paris : chez J. Cl. Jombert, Musier et Panckoucke (booksellers), 1763, pl. XVII.

2) Ferdinand Berthoud, Essai sur l’horlogerie, dans lequel on traite de cet art relativement à l’usage civil, à l’astronomie et à la navigation, en établissant des principes confirmés par l’expérience, [Essay on horology, in which its civilian use and its applications in astronomy and navigation are examined, while establishing principles confirmed by experiment], Paris : chez J. Cl. Jombert, Musier et Panckoucke (booksellers), 1763, pl. XVIII.

3) Ferdinand Berthoud, Essai sur l’horlogerie, dans lequel on traite de cet art relativement à l’usage civil, à l’astronomie et à la navigation, en établissant des principes confirmés par l’expérience, [Essay on horology, in which its civilian use and its applications in astronomy and navigation are examined, while establishing principles confirmed by experiment], Paris : chez J. Cl. Jombert, Musier et Panckoucke (booksellers), 1763, pl. XIX.

4) Louis-Jean Desprez, Vue imaginaire de l’Ecole des Ponts et Chaussées, [Imaginary View of the School of Bridges and Highways], ink drawing, circa 1770-1780. Musée Carnavalet, Paris.

[1] Ferdinand Berthoud, Discours préliminaire sur l’horlogerie [Preliminary Discourse on Horology] in: Essai sur l’horlogerie [Essay on Horology], 1763, vol. 1, p. xix.

[2] Ferdinand Berthoud, Essai sur l’horlogerie, [Essay on Horology], vol. 1, p. xlvij